The Charlottesville chapter of the National Organization for Women hosted an event Tuesday night over Zoom to present the work of Mapping Cville, a project dedicated to mapping inequities in Charlottesville over time. Jordy Yager, digital humanities fellow at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center and journalist, spoke at the event about his journey unearthing the history of anti-Black governance in Charlottesville.

Over 70 people attended the virtual talk, including several Virginians from outside Charlottesville.

Yager’s path to Mapping Cville began with his 14-year career as a journalist in Washington, D.C. and Charlottesville. Through his long-form investigative work, Yager explored issues of racial inequity locally in legal, healthcare and education systems. In all aspects, he found Black individuals adversely affected.

“Opportunities were being denied and granted to children based along racial lines at a very early age, and those decisions continued all the way through school,” Yager said.

At the heart of these setbacks was the matter of economic inequality, Yager said. The calculated cost of living for a single parent and child in Charlottesville is around $40,000 annually, without subsidies, and 22 percent of Charlottesville residents make below $35,000 a year. Of that 22 percent, white families make up 13 percent and Black families make up 54 percent.

“That is a direct result of inequitable processes at work that led to what some, traditionally, have shrugged to say, ‘This is just the way things are,’” Yager said.

Much of what Yager learned about the history of economic inequity in Charlottesville came from oral histories — meaning conversations with long-time residents of the city. Yager’s goal, then, was to corroborate these stories with hard evidence, and he found a way to do so with Mapping Cville.

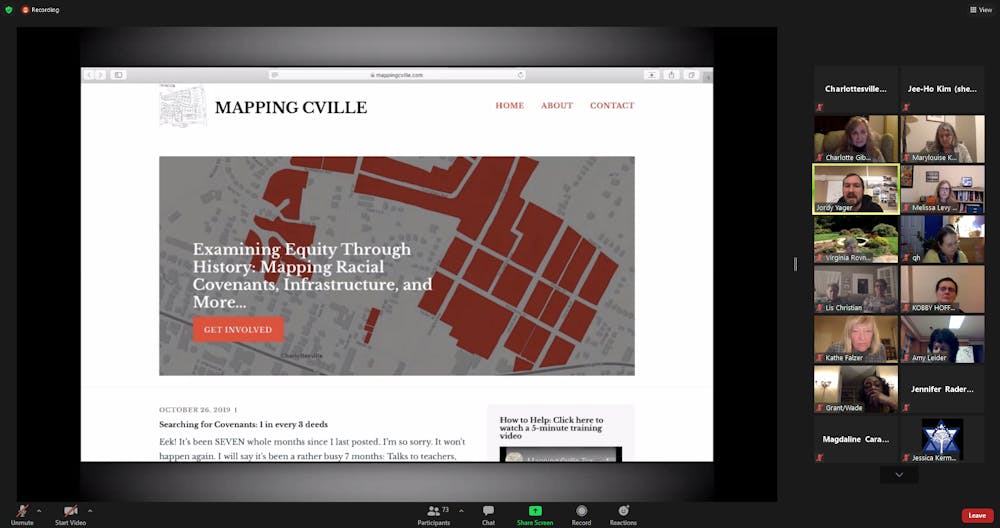

Yager received funding in 2018 from the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation to begin Mapping Cville, and since 2019, Yager has been developing a map that plots every deed that contains a racist covenant or a clause forbidding the sale of property to Black individuals and those not of white descent. Although these covenants are no longer in place, they have been found in deeds dating up to the 1940s.

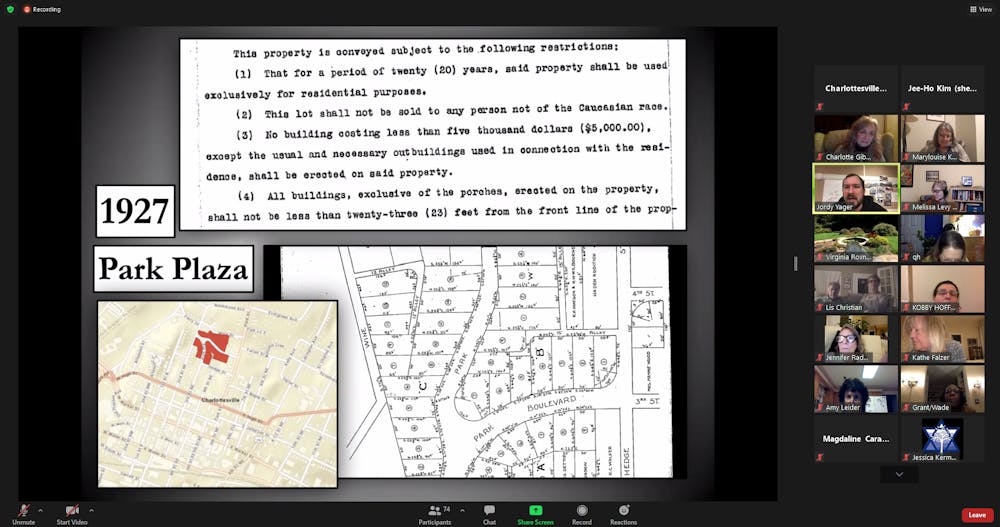

“This lot shall not be sold to any person not of the Caucasian race,” one Charlottesville property deed from 1927 said.

The records obtained by the Mapping Cville Project span from 1888 to 1968, when the Fair Housing Act was passed, which made racial covenants illegal. But in some communities, including Charlottesville, zoning laws effectively yielded similar effects of segregation. Working through the 300,000 pages of documents from Charlottesville City and Albemarle County, 1,991 parcels of land with racist covenants have currently been mapped with the help of over 2,000 volunteers. Currently, about 87 percent of the city’s records have been examined.

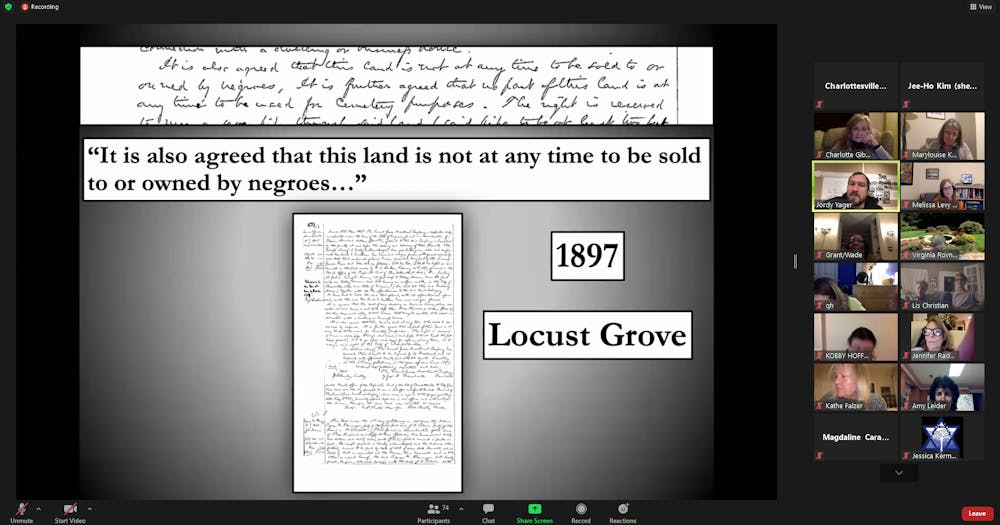

One of the earliest recorded instances of a racist covenants was found in the deeds of properties in Locust Grove in 1897 — the city’s first step towards codifying segregation.

“They’re meant to be seen as a flag to say, ‘White people, you can move here and not have to come into contact with Black people as neighbors,’” Yager said.

1915 records showed 90 properties in Meadowbrook Hills included racist covenants. Park Plaza land in 1927 included other economically discriminatory clauses in addition to racist covenants, such as requiring buildings to exceed a certain monetary value and banning cost-saving home-business setups.

Closer to the University area, residences around Rugby Road and Piedmont Avenue have been documented having racist covenants as early as 1926 and 1936, respectively.

Other work Yager has taken up includes a collaboration with Barbara Brown Wilson — faculty director of the Equity Center and associate professor in the School of Architecture — and her students to examine city investments in predominantly white versus Black neighborhoods. So far, they have found a decades-long paper trail of rejected petitions from predominantly Black neighborhoods asking for quality of life improvements such as paved streets, water lines and sewer lines.

One key point Yager emphasized was the connection between geography and life quality. Historically white neighborhoods with racist covenants have the longest life expectancy in Charlottesville at around 81 years. Historically Black neighborhoods, neglected for generations by the local government, however, have lower life expectancies at around 75 years, Yager said.

“Where one lives has a direct correlation to what happens to one in life,” Yager said.

In relation to more recent history, Yager also discussed his research on stop-and-frisk — the detainment and search of an individual by police under reasonable suspicion of weapon possession or potential crime — in the city, through which he found a notable relationship between race and geography. For example, in the historically Black neighborhood of Ridge Street and Orangedale-Prospect Avenue, there were significantly more stops and frisks than in the majority-white areas of Martha Jefferson and Locust Grove.

Once sufficient analysis has been completed, the work of Mapping Cville will be exhibited on the first floor of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center as a giant interactive map on-screen.

In March, the Mapping Albemarle project will begin, which will replicate Mapping Cville’s work on Albemarle County properties. Yager will lead this effort as well.

Mapping Cville holds workshops monthly for interested volunteers. A short tutorial video is also available on the project’s website.

“We have many thousands more documents to go through, and we would love all the help we can get,” Yager said.